Here’s a blessed event insofar as I can finally talk about role-playing content and procedures that are ordinarily kicked down the road. For me, Adept Play is a rousing success insofar as ideas can be introduced and resolved enough so that “next ideas” can actually be addressed, and I don’t have to spray down the entry point with fire-extinguisher foam or, for that matter, disinfectant.

In this case the foundation lies in Design Curriculum 9: Dice injection, my comment in Legendary Lives Debrief, and Monday Lab: Whoops (although I suspect the latter will be a callback for almost anything we discuss here for a while). Given those, we know what unpredictable, often randomized methods are for, and we know what the converse-outcomes of using them are, in fictional terms.

We kept the specific in-play action very obvious and straightforward to keep us from getting distracted by all the possible nuances of Bounce. So: as a method, we’re talking about dice, and as a fictional action, we’re talking about striking an opponent with a weapon. In other words, “rolling to hit.”

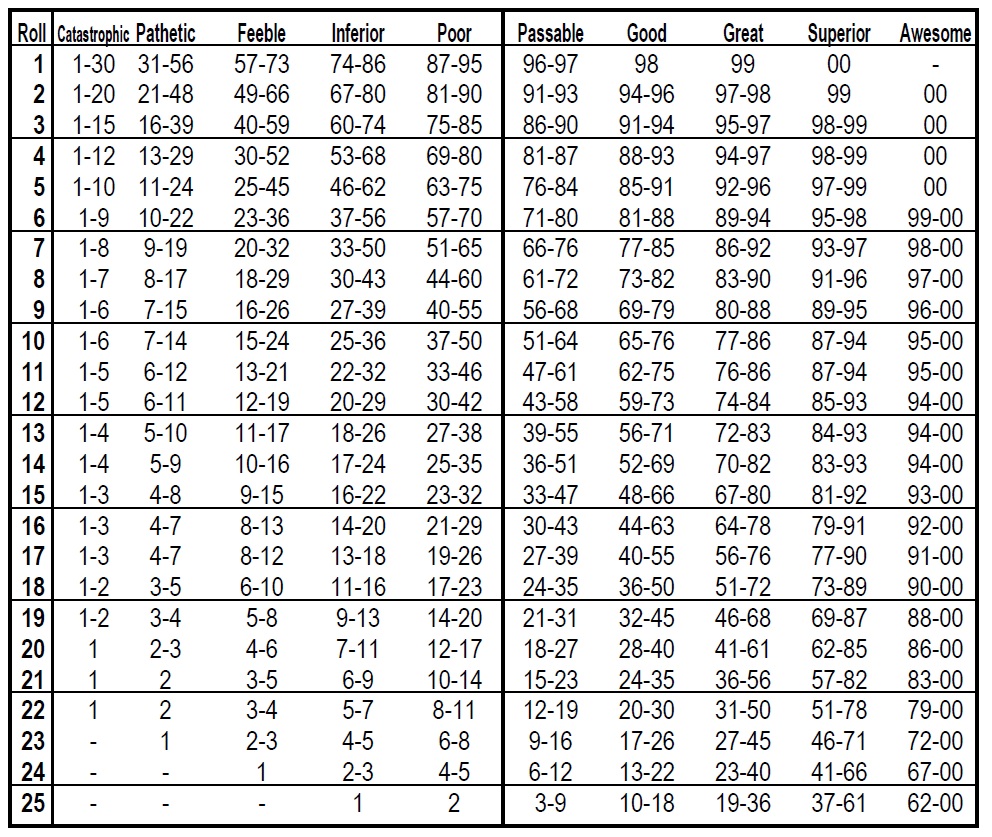

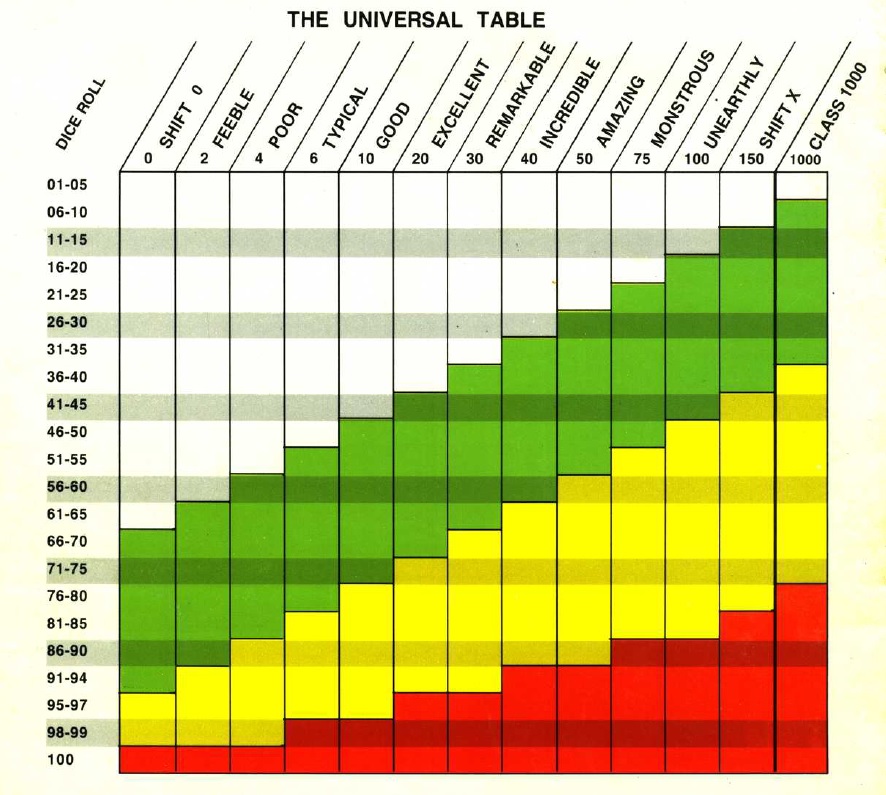

I’m especially looking for comments from Robbie, Rod, Ross, Jon, and Noah, because our main case study is to contrast the Universal Table from Marvel Super Heroes with the ART from Legendary Lives. Both of them are attached as files below, and the psychedelic knitting pattern at the top left is the ART re-presented in the same format as the MSU table, courtesy of Ross.

I’ll explain the graphic because you’ll need to understand it, and I don’t explain it well enough during the session. The horizontal axis is how good you are: worst to the left, best to the right. The vertical axis is a d100 roll, from 0 at the top left to 100 at the bottom left. The colors are the possible results, with the worst failure in white at the top left, and the best success in magenta, at the bottom right. Green is the most mediocre success.

The discussion ranges across a lot of games, with a special nod to Rolemaster which seems to have made quite an impression on three of us in the session. It also opens up a couple of things I want to follow up in some of the current consulting posts, like the difference between altering resolution probabilities and providing effect boosts. I bet you’ll find more in there too.

10 responses to “Monday Lab: Probable Cause”

Column Shifting

One of the things that sprung to mind, related to my question at the end, is the idea of how column shifting is such an obvious and visible means of affecting chances of success or chances of avoiding failure. Getting a +1 or +2 CS in Marvel Super Heroes was a very big deal and conversely, taking a penalty to your column shift was also a big deal. And the design seems so simple, but there is an elegance to it.

It illustrates something I have been thinking about, mostly with d100 systems, but the tension of failure as a by-product of play. Early in a character's life, failure is more common and possible not as deadly or detrimental as it could be. However, as one becomes a master of a skill, failure becomes less common, but the consequences becomes more acute. And there is tension on both ends of that.

And for folks who have not played ROLEMASTER or MERP (or the retro-clone but don't hold that against it, Against the Darkmaster), I will just say that I have enjoyed that system over the years, for a number of reasons. Not all of them mechanical in nature. It may not be your bag, but if you want fantasy with some heft to it, I would encourage trying it out.

It was mentioned brieflyin

(No subject)

A small observation

Oh gosh, I really hate having missed this lab. I'll keep my frustration to myself.

I'm still watching the videos (on 3 right now) but there's something about what's being said that I'd like to bring to attention, because it may bleed into what the problem seems to be in how Legendary Lives feel in play.

When Ron mentions that a +1 (+5%) doesn't mean much on a flat distribution like the d20 (d100), it could be interesting to point out that this is an effect of diminishing returns. Going from a 55 to a 60% chance of success isn't particularly exciting (and that's why you look for extra damage in oldschool D&D).

Now, going from 75 to 80% is even less exciting, because in relative terms, what was a roughly 10% increase (55 to 60) is now about 6%.

But if we were to have poor chances of success (say, 25%), that +1/+5% becomes a lot more attractive – it's a 20% increase in my odds of success.

Now, you don't see much of this in actual play because the games are written to make the % as stable as possible. The fighting-oriented characters are balanced to be hit around 50-70% of the time; the nonfighter don't really invest in +1s. So you rarely see that in play, and the small bonuses stay unattractive.

If people who have very poor skill rarely attempt at using it, and people rarely get over 18 in skill, the part of the table we're using is this:

Actually used values

What if what happens in LL is something like this? You have a huge table with vast distributions… but you don't really use that much, because you're using a rather narrow part of all that table?

The way it seems to me is that if that's the case, there needs to be a HUGE difference between what happens when I land in a different color, or shifting through columns risks ending up not feeling too different from getting a +1 in a d20 system. Is ending up in green 10% more often really exciting, if green means doing 5% better than yellow?

Haven't played LL so I don't know if that's the case, but that's what came to my mind.

A question to the “Oldtimers”

During the lab and following the discussion now I feel it difficult to separate the way we are playing (as in how much talk in comparision to how many rolls in any given encounter) from the satisfaction we get from using a certain system (or rather distribution of dice results). What I'm really interested in is (a) did the way you play those games shift, especially how often you call for a roll? If so, do you feel that shift is a general feature that influences designers? (b) Would you expect certain distributions to work better/worse depending on the number of rolls in any given encounter?

Wow, that’s quite an hard

Wow, that's quite an hard hitting question.

One feature of play during the period we're discussing (which was BECMI to AD&D2nd edition, for me) was that there was a looooot of armchair game design going on, during every session. I distinctly remember one session of AD&D2nd edition (Ravenloft was the setting) where at around 15.30 in the afternoon of saturday one character was digging a grave; he jumped in to recover what he was looking for, another character snuck behind him and hit him in the neck with the leftover shovel.

For reference, the oldest person at the table was 18, I think. Most of us between 14 and 16. Discussion took till around 21.00, then we had dinner, then we went back to play, and before the end of the session (2 am) we ended up discussing the effects of a fireball in a sewer tunnel ("Does the explosion get stretched over a longer surface, since it can't release its energy in all directions?").

I don't think it's a feature of the rules; today we'd look at sneak attack rules and be done with it. It is that (as Ron described) there was this unspoken assumption that you couldn't just pick up your outcomes and use them. It had to make sense, and that meant the DM brought in some stuff that wasn't in the rules, which means that in turn your job wasn't really using the rules as written or rolling dice or even declaring intent but explaining to the table (the DM, really, but you still had peer pressure to exploit) why and how your roll would produce a certain outcome. This was particularly true with spells because they gave you objective facts to work with: my spell does this, so logically this will happen.

Most of the time, this was a joyful and quite childish game design process/workshop we had a ton of fun with; some of the time it was just bickering and pressuring each other or leveraging real life knowledge (growing up everyone dreaded being the DM for that one guy who had become a civil engineer with a bonus degree in physics).

I feel that those games gave you very little to work with in terms of usable outcomes and instructions on failures, and the playstyle that developed was based on filling in with details and context, and I still value that as a formative experience but I have very little desire to go back to it because, quite frankly, I think it was enjoyable in a way that is intrinsically tied to the process of learning the activity and to my age when I was doing so. Expecially because it's very easy to see the experience become less about using instruments and rules to produce useful and "bouncy" information to work with, and more and more about discussing and workshopping until you persuade your GM that the "plan" actually would work, or hammer down what would happen if your roll actually succeeds in such fine detail that any outcome that isn't success becomes a sore disappointment. The outcomes get set in stone and rolls become less frequent – and while I know this may be seen as a caustic comment, I think it becomes a lot less fun because players have to play in the GM's imagination and the GM stops playing and ends up directing. There's a very strong literature about "railroading" and control when it comes to story, but I think there's an equally problematic history tied to outcomes.

I realize there’s a bit of

I realize there's a bit of text that went lost and as such a sentence doesn't make sense. When I said "as Ron described" I was referring to this message on Discord:

"@Ross (GMT +0) @Visanideth No surprise, I think, that historical pre-3rd D&D play swerved hard toward (i) amplified post-hit effects, (ii) multiple actions/attacks per round, (iii) wilder and more verbally-negotiable magical effects, and (iv) in-fiction social status and significance."

which was then followed by some comment leading to what I'm actually saying, and those got lost. But now it sounds like Ron was saying what I'm saying, which isn't necessarily true. What I was saying was that for our group (i) and (iii) were particularly big and ultimately influenced how we played to the point of leading to what I describe later.

did the way you play those

Let me answer the second part of that question first. Yes, I do think this influences design. Some feel a simple, occasional roll is the best way to handle things. Others like a complex resolution system where rolls are common and a integral part of the momentum of the game. And you can have simple rolls that happen often or complex one-off rolls. I guess what I am saying is that yes, how often a player needs to roll is a design consideration and that is a spectrum or a graph with many points along the line and axis. I would be loathe to draw any further conclusions, but I suspect “fewer, less complex, more decisive” rolls are considered a higher form of design? I reject that notion, but I think “better” and “not D&D” would be the two largest design incentives over the years and that is related in some way to the volume of dice rolling.

But BUT…

In general, no I do not think that volume matters. I suspect more dice rolling to get a result that is more dice rolling and then you look up a chart and its more dice rolling or interpretation, do tend to be more frustrating. My impression and experience is that players like “Roll to succeed. Roll for effect” and then moving on. I have noted a subconscious (I believe) ‘forgetting’ of Bonus Actions in 5E games or the playing of classes that have few bonus actions because they often require more dice rolling.

Feet to the fire, I think 3D6 is good because even subconsciously people grok that bell curve. I think d100 roll high and using the Marvel (or Legendary Lives) chart is also good, because even though its flat, there are ways to manipulate the result (column shifts) and it is a visual representation of cause and effect (or lack there of).

Legendary Lives

So having watched the seminar I went back and looked and the Lengendary Lives Action Results Table (ART), with the character sheet for my character Christabelle handy. What I notice is that a large number of her frequently used skills fall in the 7 to 15 range, which on the table equates to chances for a Passable-or-higher result ranging from 1-in-3 to 2-in-3. I don't know that I could meaningfully distinguish the impact of any of those skill variations from just flipping a coin every time. (Except of course for Sanity, where the results chart is exceptionally punitive, and effectively has a stealth 2-column-shift penalty built in — yes, my ass is still burnt about that.)

I also noted Ron's observation that the rigor of the ART about applying specific and immediate consequences, which I take as one of the game's appealing features, is also responsible for contributing to the whiplash feeling of events in play. Not sure what, if anything, to do about that.

Since no one else in the

Since no one else in the session was familiar with Legendary Lives through play, I missed about twenty things that could have clarified or specified topics that arose. Also, the re-configured presentation of the ART continues to need discussion, especially with the numbers placed on the axes and the range of real player-characters' abilities marked out carefully.

If we had that, then I think we'd see exactly what you're talking about: that within the range of most player-characters's abilities ("Specialties" in the game's terms), the distribution falls between 33 and 66 percent, with not much curve involved at all – the most-common colored bands are essentially diagonal. Which is, basically, a coin-flip, with Awesome and Catastrophic cropping up who-knows-when, and often, in fictional terms, out of nowhere.

I think I remember at some point in our during-play/after-play discussions, I talked about Marvel Super Heroes "qualitative descriptor" range running mostly in the superhuman range, so that the lower values were not "bad," but pretty much like regular people doing regular things. So most of the range concerns super-things (powers, skills, prodigious intelligence, et cetera) in opposition, and very little about the range one might conceive for doing ordinary things. Whereas in Legendary Lives you're applying nuances of success and failure very much about doing ordinary, non-super things, so you're getting the kind of spectacular successes and failures that make more sense for a mighty thing that you're using strictly in crisis.

You're right as well about the odd pairing of the specific ART consequences with its arbitrary-seeming statistical features. The historical role-playing solution is to abandon the former in favor of exactly what Greg was talking about, to let the GM adjust and basically determine what the outcome means as they see fit. Whereas I would rather preserve the former and seek solutions in changes to the latter.

With that in mind, I think I'd like to try out an ART with much more curvature "in the middle," so that the column shifts Sean is so excited about punch hard in play when they apply to something in or close to the median value, much like a +1 or +2 does for an 11 or less on 3d6.

P.S. Yeah, the Sanity rules are way too brutal. I'm not sure why or how that got into the system; characters' freak-out and actual clinical breakdown doesn't seem to go with any other aspect of the system or concepts in the setting.