Our Forge: Out of Chaos game continues. We decided to wave a magic wand and advance the characters to what seems like a reasonable “next tier” of effectiveness, giving Robbie’s magic-using character Cyir Level 3 with his Magic skill and Sean’s roguish/scoutish Wrosk improvement throughout his repertoire of skills. We made this decision after coming to the realization that by sticking to the advancement rules as written, we would need to play for several years before Robbie’s character would have access to much more than one or two low level spells per session.

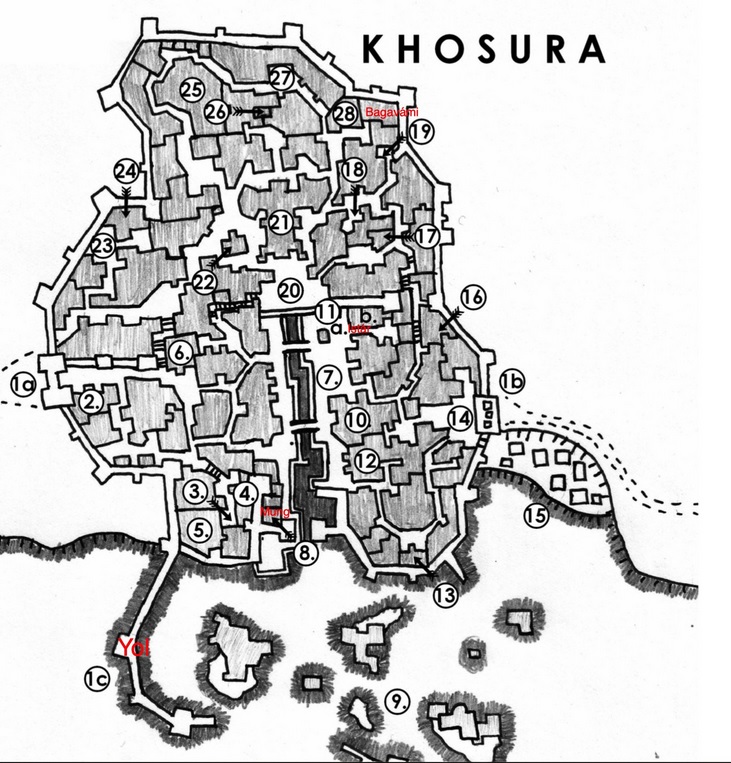

I wanted to run a few city-style sessions, and Robbie and Sean were willing to humor me. The material I am using is from the write up to Gabor Lux’s Khosura from Fight On! Magazine (the city itself is described in issue 9 and the catacombs and dungeons beneath the city in issue 10, with an additional dungeon “sub-level” from issue 1), along with his collection of random encounters for cities, The Nocturnal Table. In adapting this for Forge, I’ve simplified things quite a bit (mainly by stripping down the number of factions in play) and replaced the creatures/monsters with some of my favorites from the Forge rulebook.

I don’t have too much more to say about the game in general at the moment, but I did notice something while watching our most recent actual play video that I thought might be of interest as a topic for reflection/discussion: I don’t like watching videos of myself, in general, and I’ve found I have an even harder time watching videos of myself trying to GM. However, I was going over the most recent video for our Forge: Out of Chaos game to refresh my memory about some details to aid in prepping for the next session, and made an interesting observation.

At the very beginning, you can see me struggling to set up the scene, not quite getting on how I want to present the information, wanting to give enough context to provide grounding for meaningful decisions, as well as wanting to get flavor/mood/color details across, but almost completely at a loss for words (painfully repeating the same non-information over and over again). Then at around the 4 minute mark, I decided that what I was doing wasn’t working and should just start in with the scene: i.e., stop being abstract, stop providing context, and focus on what the characters are doing, where they are physically standing, which NPCs they are currently interacting with.

Everything started working at that point! I don’t know that I would generalize from this to say that one should always avoid more abstract scene-setting, but I think the video is a nice example of someone struggling with murk and then refocusing on the basics of the medium to de-murkify the scene.

The embedded link goes to the most recent session and here’s the link to the playlist.

6 responses to “Arbitrary Advancement and an example of a GM lost in the murk”

It looks like this and you are here

You've provided an excellent companion experience to our game and discussion of Dialect, which I think showcases this issue as a design flaw, especially in comparison with their otherwise sharp and clear delineation of authorities (who and over what).

If it's OK with you, take a look at the opening moments of any of the Spelens Hus RuneQuest game sessions or the Undiscovered sessions, both of which absolutely require sensory grounding and a clear common ground of "where, who, and who is exactly where" for play to occur at all.

This last weekend I ran a

This last weekend I ran a convention game and this was on my mind. I watched the 4eR Pyschadellic videos because I was curious again how you (Ron) got follks focused and headed in more or less the right direction. I will go back and watch the RQ and Undiscovered videos.

Jon, I was going through this a bit yesterday when I ran the 3.5e game for Helma and Tommi. In our second session I was having a bit of trouble trying to tap into the energy from the first session and keep it going in the second, which I am not sure I did a good job of. From a player perspective, I did note you seemed to be trying to find good context for us and what was going on, and I think you did that. We were moving to a totally new place and we had a bunch of baggage from the previous set of sessions to take care of before we could get rolling. So that was a lot that you had to juggle before we got into the new content.

Useful specimen of play

At least the first four minutes, which are all I've watched. I recognize that impulse to contextualize, as if providing background and reminders and meaning for everything up-front is what will get play to go, as opposed to the concrete elements of play, as you've identified.

Thanks for calling that segment out; it's very informative and a great reminder.

Heartbreaker reflection request

Jon, we've talked before about the charming or intriguing features of this game (technically I guess my first step in that conversation was in 2003), but I'd like to know more about it in contact with human hands.

Can you provide any thoughts about playing the game, as an experience? Fantasy as such, content of any kind, rules options, mechanics in action … anything, but I'm not demanding anything specific. I'm also more interested in free-associated musing than a reasoned essay.

As I’ve mentioned, this has

As I’ve mentioned, this has been a bit of a learning process as much of the material from the text that I found to be inspiring hasn’t fully made its way into play yet: starting as beginning characters kept a lot of the more colorful and situation-altering magic out of reach and I overused undead in my prep. I had reasons for this — one of the important NPCs was a necromancer — but in retrospect giving a more prominent place to some of the weirder creatures in the book might have been preferable.

With that out of the way —

I think we’ve really grabbed onto the distinctive parts of the game that we HAVE put into play. For example, from reading and thinking about the game, I found the non-standard player character races to be inspiring for a couple of reasons: (a) as I’ve mentioned, they look like they could have stepped off the cover of a metal/prog album from the 70s; (b) there’s an interesting range of “obvious bad guys” to “seemingly standard fantasy heroes” available to play, but there is no actual advice or instruction that you have to play them in any particular way, opening up the idea of playing them very much against type. (It’s important, for example, that a Dwarf can end up being a Grom Warrior and a Higmoni could be a Berenthenu Knight). And the two PCs have been very cool and distinctive in play: their special abilities really matter, and the weirdness of them makes it hard to play them as merely, say, “reskinned” elves or hobbits. I like the way Sean has taken the basic description of what a Jher-ems “is” and used it as the basis for a very interesting (and genuinely strange) character. That there isn’t a ton of baggage on what a Jher-ems is “supposed to be” (again, compared to, say, what a dwarf is “supposed to be” in this kind of game) it seems to give us a lot of freedom to play around with and make something very cool out of this weird collection of descriptions and game mechanics (i.e., the mechanics around his poor vision and his telepathic abilities have been hugely important in play and in terms of his characterization).

I really like the very sketchy world and the metaphysics/mythology of it, even though that part is kind of goofy. and the setting as presented in the book gives you nowhere near the kind of juicy stuff to play with that Legendary Lives does (or Darkurthe Legends seems to based on my reading that and watching the videos of the game you and Robbie played in). The premise in the core book pushes the idea that the game takes place in a post-apocalyptic wasteland, ravaged by gods warring among themselves after unleashing terrible magic (again, the kind of prog/metal album cover stuff that I love). I did end up buying, for this game, the official world sourcebook, which was, unfortunately, very disappointing: the post-apocalyptic element there was dialed way, way back, and what it offers is a more standard Gygaxian fantasy atlas. So though I looked through that material, I ended up deciding to go my own way and use the sketchy details pieced together from the main book as an outline for me to fill in different details.

As an example of how I filled in details or riffed on one of the presented elements: part of the cosmology of Forge is that after the god war, some gods are simply absent. However, the schools of magic they created are still practiced by mortals who have kept some of the old knowledge alive (this is called Pagan magic in the rules). That’s in contrast to the Divine magic, which is directly granted by one of the two gods who are still in the universe (though trapped in the underworld). What I have taken this to mean is that the Pagan tradition is very much human centered and thus political: the various cults passing down this knowledge profess allegiance to the absent gods who founded these magics, but that profession is somewhat ceremonial. All you have to do to master Necromancy is to follow the procedures and rituals of Necromancy, you don’t have to actually have a specific relationship with Necros, the god of death, even though, in my formulation, the Necromantic cults at least put on a show of worshipping Necros still. Whereas with Divine magic, the political element is simply not there: the magic is solely based on the magic user’s personal relationship with and adherence to the demands of Berenthenu or Grom. This makes both Berenthenu Knights and Grom Warriors dangerous and mistrusted: they are pursuing abstract goals which are not in themselves political. I was thinking along these lines before bringing in the Khosura material to work with for the recent sessions, but it is a good fit for the kind of cynical/world-weary sword and sorcery presented there.

Writing this out, it may seem like I put too much thought into this, since Forge is designed for fairly straightforward dungeon crawling in most ways. However, I think it easily brings out this kind of elaboration, which in turn helps to give an interesting context to the dungeon crawling. (As I think I mentioned before, when I was prepping for this game, I was consciously trying to avoid making a situation where the dungeon was merely an arena for competition — like a video game level — and was trying to ground the dungeon crawling in human concerns. I was also probably subconsciously influenced by reading a lot of Runequest stuff while I was prepping our first sessions).

Playing the game, I find it to be very, very tight: it seems like it has been fully baked through play, and the text is very good about dealing with most of the edge cases in the rules that we have come across. Part of my enjoyment is just knowing that we can do what we’re doing without worrying about the system not being there to support us. We’ve leaned heavily into all of the mechanics that the various choices we’ve made during character creation and scenario prep have pushed forward on us: namely, lots of use of the perception rules about the various kinds of vision (and Wrosk’s telepathy) and a central role for the reaction chart (Cyir gets a bonus to it as a Merikii and it has been very meaningful that he makes friends so easily). And I’ve made creative use of the saving roll system to help guide my play of NPCs when they are faced with various morale-threatening situations (which is implied but not necessarily outright stated as something you should do). Since we decided to “level up” between the first chapter and the current one, we are just now seeing Cyir getting to wield magic that is truly situation altering rather than being merely an attack. (Although several NPCs did have access to situation altering magic in the earlier sessions, they didn’t have much of a chance to use it).

One of the things that is worthwhile in the experience is that while it is D&D-adjacent in terms of the assumed content of play, its procedures are very clear and very much its own, which means that it mostly keeps me from falling into the trap of doing things a certain way because of assumptions I’m bringing to the game from other games. A rare example of me falling into the trap has come with the bleeding rules: I felt were unclear in the text, but, in retrospect, I realize the issue is that I assumed it would be handled differently because that’s how a D&D type game would handle it and I couldn’t process the fact that it was clearly doing something different. Anyway, I botched the bleeding rules and several NPCs who survived the initial dungeon delve probably shouldn’t have (although had we all understood the rules at the time, the players may have taken steps in preparation to deal with bleeding characters and so might have saved these NPCs anyway).

There are still things I’d like to see more of: there are a lot of combat skills that have yet to come into play because of the two PCs’ focusing on magic and stealth/perception rather than fighting. I may try to bring some of that forward with some NPCs who are about to make more of an appearance in the game. And the monsters I’ve populated the catacombs of my version of Khosura with include some of the weirder (and more dangerous) creatures from the core text that I hope will be a little more flavorful than the zombies and skeletons we’ve seen so far.

Those are my musings off the top of my head. If I had to summarize, its strengths in play for us are the weird stuff around the edges (in terms of character creation and magic skills and the sketchy cosmology) and the very clear procedures for making things go. I’m enjoying it a lot.

I’ll move past all the thumbsI’ll move past all the thumbs-up “yeah” moments for me in this description, to focus on this bit:

I think there’s more going on here than you (or anyone) layering more content onto a simplistic game. I think you’re on-target in identifying rich or at least usefully extravagant content. It so happens that I’m working up the pedagogy for a class to be taught later this year, and part of it is relevant. I’m considering the strong belief, or faith, across the decades of RPG design, that fantasy (imagine this word in classically flowing and psychedelic script) can be discovered and created through role-playing … if one “solves” D&D or “does D&D right” as a first step.

Heartbreakers are raw and honest in this belief. Some of them tack on dungeons and treasure-hunting as a sideline or starting point, some of them (like Forge: Out of Chaos) stay solidly in this sphere in terms of rules and examples, and some of them only nod to it in certain ways, but it’s always there. And yet also, always, the heartbreakers see and show bigger and odder vistas of fantasy on the horizon, or just above, or right here in bits and pieces. I don’t mind that the implied and partly-visible, partly-doable fantasy in Forge: Out of Chaos is distinctly youthful and undisciplined; to the contrary, I like it all the more for these things. What matters to me intellectually is why they don’t just start there and do that.

I know the answer. Because, by the 1990s, fantasy is D&D is fantasy, and no one is stuck harder into this gluey tautology than someone who seeks more. They know that the titular game itself isn’t going to do it; it merely bloats the promise into bigger and bigger forms. So they launch into discovery for themselves, but instead of escaping the tautology, they embrace it, they go further in … and what you get in a fantasy heartbreaker RPG yields, not always but much more often than not, a surprising degree of success.

Not without its painful residue, however, in the play-and-design. The grip of all that coin-collecting, the pro forma vermin fights, mating the concepts of band-of-rogues + epic doings afoot, and the no-effectiveness to start is very strong. The slow, odd improvement in Undiscovered and Forge: Out of Chaos is a good example, especially since they both do include somewhere quite fantastic to go.

Another variable that makes sense in this context is the curious role of elves and dwarves in these games, which varies across three distinct paths. In Fifth Cycle and Legendary Lives, they’re “just another kind of person” which doesn’t match literary fantasy at all; in Forge: Out of Chaos and The Crossroads of Eternity, they’re bland and completely unrelated/uninteresting to any of the other content, which is a hair away from being absent (as in a couple of other titles); and in Darkurthe Legends, they’re central to the setting and taken up to 11 in pure fantasy impact.