On Monday, we played session 51 of the game I wrote about here (and also here). The game feels like it’s reaching a conclusion, and I’m looking forward to wrapping it up by session 60.

For the sake of convenience, I call each sequence of 10 sessions a “season” as in seasons of a TV series. Even though there is no pre-conceived idea of what will happen or whether that arbitrary breakpoint will produce a unit, it has often worked out that we hit some of the most dramatic and climactic turning points as the seasons turn, and session 50 was very much like that.

For the first 6 sessions, we were playing LotFP Weird Fantasy RPG.

After that we switched to LotFP-flavored Freebooters on the Frontier, a Dungeon World variant by Jason Lutes, based on player feedback. Basically, two vocal players pushed for Dungeon World, and the rest were open to playing just about anything in the vein of “D&D”. I also found one pain point with LotFP, but if it was just that one thing I would have been happy to stick with it. I would love to run LotFP again!

I offered to run Freebooters rather than Dungeon World vanilla because it removes some of the features of DW that make the characters feel like epic heroes—such as Last Breath, rapid healing, and lightning-fast advancement—and reworks the game to offer a more human-scale adventure game where surviving a trek across untamed wilderness could itself be desperate. That was in line with some of what I wanted when I offered to run LotFP.

Re-skinning and customizing Freebooters to make it coherent with the established fiction made it play very different than a typical Freebooters game, I think. Part of the need to customize came from the desire to match the way magic looks and feels in LotFP, with a lot of influence from D. Vincent Baker’s supplement The Seclusium of Orphone of the Three Visions, but we found other sublte revisions that suited us too. Here is our current slate of common “moves”—the rules that expose the expected adventure situations and tell you how to resolve them.

Another departure from “standard” dungeon fantasy role-playing was introducing domain-level play from near the beginning.

The players developed intense political ambitions for lowly freebooters, ambitions that promised to be matched by a vivid and complex machiavellian backdrop of warring clans and diplomatic intrigue.

Trouble is, I didn’t trust my brain to create enough differentiation between machinations of the dozen-plus factions in play (which was already established). Hearing the hype about the faction mini-game from Stars Without Number by Kevin Crawford (from this video, maybe?), I began to wonder if there was an easy way to graft that into our weird fantasy setting.

Early on, someone pointed me to another game by Kevin Crawford, An Echo Resounding, which provides a framework for faction development in the vein of SWN with a sort of “feudal orient” backdrop instead of spaceships.

I jumped in with both feet. Instead of taking on the faction game as a GM prep exercise (too much work), I decided to crowdsource it by letting strangers online play each faction—setting their own diplomatic agenda, stirring up their own schemes, and launching their own wars. They also developed a lot of setting detail for the factions they controlled, including in some cases vivid characters who have played roles in the tabletop game.

As a consequence, one player started calling it “Game of Khans” (echoing a popular HBO series). The response of the players in the tabletop game was stark: As they discovered the outflowering of each faction’s actions in the domain game, they all grew to appreciate the game in terms of what Tolkien called a subcreation: Knowing that most of the factional politics was out of my hands gave them an immersive respect and enjoyment of the world as a persistent and concrete virtual reality with its own integrity. And a few of the tabletop players have been very active in domain-level diplomacy and scheming.

Those two interlocking systems—Freebooters on the tabletop level, supplemented by an asynchronous game of An Echo Resounding to flesh out the backdrop—has produced an immense amount of drama that cascades back and forth across the different scales of play. I wouldn’t want to make this kind of supplemental Diplomacy-type play a standard feature of my role-playing, but I would definitely try something like this again one day.

For sessions 33–37, we took a break from Freebooters to play the new Usagi Yojimbo game by Sanguine, using the same setting as a backdrop but seeing (and mostly shaping) events through the eyes and roles of different characters. After that, we returned to the Freebooters characters, one of whom was rescued by the Usagi Yojimbo crew.

Events in the tabletop game and the domain game suggest that we are approaching the end of the run. There seems to be no limit to the political ambitions and intrigue the tabletop players may be willing to explore, but this campaign has answered most of the questions and resolved most of what we wanted to find out. This game was, after all, framed as a prequel to a previous Dungeon World campagin that spanned ~30 sessions.

Another thing is, we can’t count on the central players being able to schedule games together indefinitely, even if we wanted to spin up one adventure after another without any conclusion. I’d like to wrap it up in a satisfying way before we have to cut the game off due to inevitable life and schedule changes. If that leaves further mysteries to explore in another campaign, I’m okay with that!

6 responses to “Dark World after 5 seasons!”

Oh, is that all?

I did ask people to "talk about their game," didn't I! This is pretty amazing. It's also an instant partner to Tommi's recent post, in which he has played characters more-or-less freely through a variety of systems and groups.

Over the decades, I've seen a few versions of this process, in which a given group, or more accurately, one person through slightly-shifting groups, keeps playing the same fiction through system after system. As I've seen it, especially back in the 1980s and 1990s, the process was driven mainly by desperation. (real example) "AD&D isn't working, so here, Rolemaster is clearly the better and modern system, so we'll use that, but look, now, GURPS is finally the universal 'last game you'll ever need,' so let's switch to the Fantasy supplement for that," and so on and on. In this case, the main or organizing person was driven by the desire to produce a published setting and even a novel (or series), and the failures of systems to meet this expectation for him was not only a motivation but an escalating source of anxiety.

Sometimes this process is tacitly under way even when the fiction isn't continuous. (again real-world example) That's why we played Rolemaster: Space to play cyberpunk stuff around 1987, before Cyberpunk was published, which we played right away, and if we hadn't moved apart physically, I suspect we would have switched to GURPS: Cyberpunk a year or two later. In this case, although the characters and fiction weren't connected between the two games, clearly we (meaning two groups overlapping in membership) were determinedly seeking a fixed aesthetic or experience in the same way as the continuous-fiction fantasy example above.

By contrast, your less-stressed, even a bit whimsical willingness to shift over and around systems offers a chance to look at the necessary and interesting outcomes without fears and expectations muddying everything. It will take me a little while to write more specific questions and notions, but so far, that's where I'm coming from.

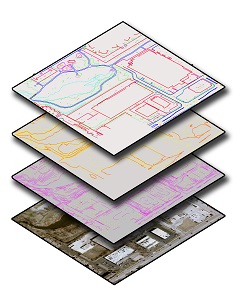

[The image of layered maps

[The image of layered maps you added is perfect!]

That makes me wonder about my motivation for expressing different sides of the setting in different systems.

The first shift in this series wasn’t swapping out LotFP for Freebooters, it was layering on the Diplomacy-like domain game with An Echo Resounding.

That was motivated most of all because there were players with big political ambitions, and the setting promised them a complex web of politics. It comes of being reckless. When the Lizard King died, I narrated that nine khans and their retinues converged on the city to determine a new king. I could have said three or four instead, but I said nine. In that context it was just as easy as saying zero or a thousand. 🙂

Now the players wanted to: 1) Unite the khans, in order to 2) end the slave trade, and 3) drive the Tsaritsa and her forces off the continent; for 4) one of the player characters to become king. That’s not to mention all their personal ambitions that could have political ramifications against that backdrop. Not only that, but in session 3, they were already asking for a war summit with the nine khans and other sovereigns!

Suddenly, I knew I was in a spot. The nobles they rescued during the first mission would have the motivation and clout to call a war summit. And I really wanted to portray all the delegations having their own vivid interests, rivalries, and tensions—both orthogonal and colliding. And I expected that if pressed to develop those personalities and intrigues out of whole cloth, in my limited creative time between sessions, it would feel flat and same-y—at least to me.

The selling point of An Echo Resounding is that it’s not meant to be a different system for resolving stuff at the table (mostly). Instead, it’s supposed to be a tool to help the GM set up a dynamic relationship maps on the scale of border kingdoms. The idea is, you set up a map with a half dozen factions pursuing their own interests, the players can go anywhere and form their own sympathies or enmities; and eventually (in a Labyrinth Lord game, which AER says it’s compatible with) the player characters will be tough enough to establish their own domain-level assets.

What I did was I created a new Discord server and invited a bunch of people to take the roles of the dozen-plus domains. Most of the domain players got to choose where their settlements were on the map, like in Settlers of Catan, and they got to determine their specialties and assets using the rules for AER.

I asked the khans to each choose another clan they had enmity with, one they distrusted, and one they held no current ire for. They immediately erupted with ideas for their unique cultures, customs, and other fictional color, with some inspiration from the established fiction. And they immediately began sowing intrigue and buidling alliances behind the scenes, like it was a game of Diplomacy.

This solved the exact problem I hoped it would, and delivered a lot more than I could have imagined. In the very first domain turn, two different factions sent invading armies to their unsuspecting neighbors and annexed new territory. This happened close enough to where the tabletop players were that they got wind of it—it had a huge impact on their immediate goals and actions.

When the war summit happened, the domain players held a day-long real-time convocation on the Discord server, where grievances were aired, intelligence shared, war plans laid, and military assets pledged. But for the tabletop players, it revealed just how fractured the federation was, and how hard they would have to work to eke out any of their political ambitions. And, just then, a devastating plague began sweeping across the land to make things worse. (This was at least a year before our real life pandemic.)

Besides outsourcing creative direction and scheming for the factions to other players, another difference between what we have done and AER’s presumption is that we dispensed with the level-based notion that freebooters could have a domain when they were tough enough. Anyone could take part in domain stuff as early in their leveling-up career as they wanted, provided they could get domain-level assets, either through trickery, conquest, or getting the domain players to share.

One of the tabletop players got involved in that right away, and has been leading armies and commanding farflung spycraft. Another, nominally a prince, showed some interest but alienated half the domain players due to paranoia.

I appreciate the detail. I

I appreciate the detail. I want to clarify that I'm not questioning your motivations, but rather contrasting your experience with the desperate (possibly neurotic) versions of system-switchups that I'd observed in the past. I'm still working out things I want to ask you specifically, but it's turning out a bit harder than I hoped.

Retainers in LotFP

My one pain point with LotFP was with retainers.

The situation was, the Tsaritsa captured and occupied the castle of one of the player characters, as I described in the session 1 recap linked above. The high-Charisma Magic-User fled, attempting to recruit followers from nearby banditry to rescue some VIPs imprisoned there.

One cool thing about LotFP is that there is no limit on the number of henchman you can recruit as a player character can recruit, provided s/he can find classed characters (implied to be rare), and offer them something worth possibly dying for. Their recruitment and loyalty hinge on your Charisma and the generosity of your offer, and according to the rules you don’t need to make a down payment. The catch is, you have to be at least 2 levels higher than the follower, but we started everyone at level 3.

In this case, the character had +2 modifier from Charisma and offered to let them take ANY AND ALL treasure they could loot from the castle.

As a consequence, he was able to muster more than 20 Fighters and Specialists, which I generated using Ramanan S’s LotFP Character Generator. (I don’t remember the exact number now.) That meant a lot of rolls to establish whether they accepted the offer and what their Loyalty was—some number rejected the offer. We resolved that between sessions, and it was no big deal.

It was really cool to have the Magic-User return with a bunch of minions to assist the other player characters. And for the most part, it was no hassle having them in the game. A few of them developed interesting personalities as we interacted with them, and most of them were mainly there as fictional positioning. It totally changed the dynamics of the rescue mission from dungeon raid to a more calculated and less risky assault.

The trouble came up whenever there was an event that would trigger morale checks. Since these people had never seen magic before, there were a lot of chances to be unnerved by the events inside a castle covered in elemental living nightmare.

What happened was, at the key points when some major escalation of danger prompted a morale check, I rolled for each and every henchman. As you might imagine, making 20+ rolls each time felt like a slowdown.

In hindsight, I noticed that the rules for Morale checks state that a check can apply to an NPC, monster, or a group of monsters. While strictly speaking, the henchmen were marked up as classed characters and not monsters, I think applying the results of a single roll to the whole group would have been within the spirit of the rules.

I think the reason I didn’t think of this at the time is that each henchman had their own Loyalty score affecting morale. I can think of a half a dozen workarounds for this that don’t require rolling 20+ times for every check, I just didn’t think of it at the time.

If we have a big group of henchmen and/or retainers next time I run LotFP, I’ll make sure to have a house rule in place to clarify and simplify this, so the morale check can be resolved for the whole group more easily.

For the players who favored Dungeon World, this issue was added to the evidence that LotFP was too fiddly.

In our online Coup de

In our online Coup de Greyhawk play we have often had five to ten henchpeople/retainers and it has gone reasonably smoothly. Some player has been making essentially all rolls for them and keeping track of their hit points, just like some player is writing the log, someone calculates experience shares, someone maps, and so on.

We have also had the benefit of an online dice roller – just ask it go give ten attack rolls or morale rolls or saving throws; the results of most are obvious and for the rare few we have to check the bonuses of exactly that person to see if it succeeds or not.

We do default to NPCs having a ten for all their stats unless otherwise established. Non-levelled people rarely get established with any more accuracy than that and only a few retainers have had levels.

The hard thoughts inside

My thoughts on this topic are still not coming together, and I'm more sure that I need a Monday Lab for it. The scary or loaded content includes the term "compatible," which has been an ideal or assumption on and off throughout the hobby … like, whether any and all RPG systems are necessarily compatible, or assuming that compatibility is only an issue because this or that system is "flawed."

These pro-compatibility ideas run into trouble in the face of titles/systems for which flat-out incompatibility is a desired feature rather than an assumption or goal. And even more so regarding the subtler, painful reality that designing improved or better functions necessarily criticizes previous versions and other titles.

In other words, let's say Game X gets a new edition, and for simplicity's sake, let's even say it's not purported to be a massive re-imagining or redesign, merely, you know, "the new edition." Well, what is that supposed to mean? Is it different or not? If it is, then that triggers defensiveness; if it isn't, then why bother buying it.

I've generally observed long-running sequention editions non-D&D titles to rely on plain old duplicity through omission and tapdancing. "Yes, it's different, no, we're not saying it's better, yes, it's revised and improved, no, it's still compatible, yes, you should buy it, no, you're not less awesome because you played the old one," et cetera. There seems to be no other option unless you're willing to come out and say the old one was flawed.

Anyway, you can see how the topic runs away with me. This kind of sequential edition issue isn't what you're posting about, but it's one of several related things that gets drawn into it. I think I'm bringing it up as an easily-tracked example of the "playing through many systems" topic.