Jon made the mistake of musing online about playing The Pool with a Sin City, To Live and Die in L.A., Haven: City of Violence way, and like two predators spotting the straggler, Sam and I struck. Jon’s introductory sheet is attached, and so are our starting characters, created after reading it.

Jon made the mistake of musing online about playing The Pool with a Sin City, To Live and Die in L.A., Haven: City of Violence way, and like two predators spotting the straggler, Sam and I struck. Jon’s introductory sheet is attached, and so are our starting characters, created after reading it.

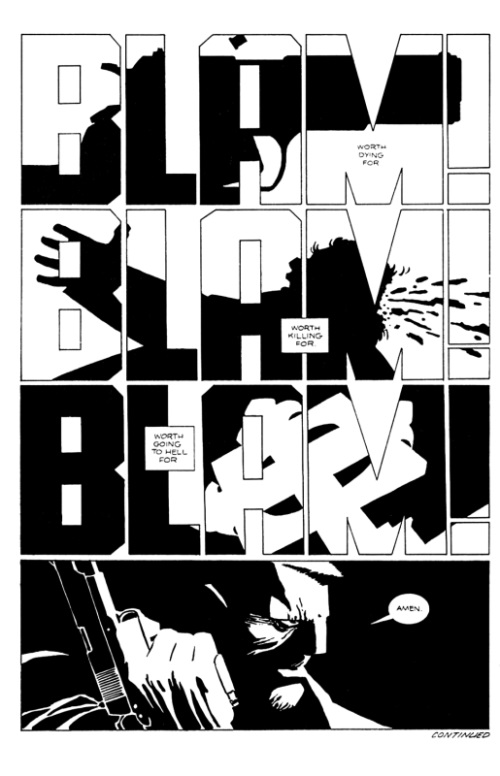

As you’ll see in those files, Sam and I did not create any Marvs or “deadly little Miho,” opting instead and independently for shifty grifters. Unlike the image I’ve chosen, there has been no “blam blam blam” … yet. We play for one-hour sessions and so far just one. So the night is young, so to speak, and if our fast-talking characters keep talking so fast, one of them is likely to walk right into a page like this one and very likely not walk out.

As far as “let’s talk about The Pool” is concerned, I draw attention to the clear secondary role of speaking when you’re not the authoritative contributor. I’ve decided this is a serious sore point in role-playing generally and, as with so many things, merely thrown into more obvious form by playing this game.

Here’s what I mean. Let’s say Bob is understood by all to be the opener of scenes for this game (one application of situational authority). Bob says where we are, who’s there, et cetera. Now, two kinds of secondary speaking may be involved.

- When someone else’s input is necessary for Bob to do his job. Bob either asks or simply expects people to say what their characters are doing or would be doing since last we saw them, and uses this information to open the scene. It’s still up to him, including accepting, subverting, or interrupting whatever was said, or even just doing something else, because the input is provisional and helpful, not a negotiating position. It’s also necessary; Bob can’t do this job without it.

- When Bob has it well in hand, as we all know and value, but someone pipes up, “peanut gallery” style as I say in the video. It’s pure table-talk, acknowledged as flotsam and jetsam, perhaps merely sharing how that person imagined things, sometimes only obliquely about the played moment, and sometimes an outright suggestion. But always totally provisional, known to be no-obligation, merely conversational atmosphere unless Bob says “ooh! yes, like that,” or partly so.

Opening a scene is merely one of the hundreds of inputs into play for which this point applies. Anything that anyone says – always. This isn’t a player/GM issue but a feature of the medium. [adding instrumentation for constraints on what you say can be put anywhere you like, like rolling to hit]

Neither bullet involves consensus in terms of content. I distinguish very sharply between (1) required input and application vs. (2) consensus. Bob cannot say what I should say, and I cannot say what Bob should say. We have to hear what each person says and sooner or later play will reincorporate some of what we heard, i.e., we’ll say something more about it or its effects.

If you’re just nodding along, “yeah, yeah, uh huh,” then I ask you to reconsider. What I’m describing here, which I consider completely healthy and even necessary, is not favored by our hobby culture and its concept of The GM. It’s related to equating talking with control, and more than one person talking as competing for control. 2021 brought me several remarkably bad experiences in play when the Bob person barely tolerated the first bullet, so that “what do you do” was extremely pro forma, sometimes perceiving this input as distraction to be smoothed over; and they reacted to the second bullet as an outrage upon play, spoiling it, or showing off, or defying them.

Check out the way we play in these. It is definitely not consensual storytelling, i.e., a festival of how-abouts and negotiated agreements. Nor is it a fierce competition for who controls anything. We have our jobs, and we can’t do them without each other.

17 responses to “Bad doings in Bulwark”

Excellent Play

I like how authentic the two characters are and how so much like the source material this is.

Just a thought or observation on Ron's point. I think when play is working and the players and GM are all in tune or at least, on the same page, that table talk, no matter how off-track it might appear, does contribute to the ongoing fiction. Because the juice is flowing right? Personal goals / agendas are aligned? Maybe what I am trying to say is that good play, which can be more rare than folks think, might appear to the outsider as one or another person asserting their will on play, when it is in fact just people grooving in the same direction.

Hope that makes sense lol.

Rather than “grooving” or

Rather than "grooving" or "same page," pleasant as they may be, I know what the baseline requirement is for any group to arrive at their preferred and functional profile of table-talk. It is to understand how the authorities are arranged or configured first, and for everyone to know that we all understand it.

When that's the case, there is no fear of disruption or confusion over whether X was said (diegetic) or immediate negotiation. How much yipyap we do, and about what, can settle into some supportive and enjoyable form. I agree completely with you that this is desirable and, as I see it, play is quite naked without it.

This comment is just hitting the conversation with a stick with a term written on it, which isn't much of a dialogue. But I think it will work better to be more illustrative and specific in my upcoming reply to Lorenzo, so keep an eye out there.

Joy!

This was incredibly fun to watch. I have a massive backlog of videos I want to watch on the site, but the premise was so interesting and the people involved so cool that it skipped ahead in the line. It was worth it – it's one of the most fun let's play I've seen (as in not just interesting or informative or enjoyable, but actually fun to watch).

The only bad aspect is that Sam was often hard to understand; his voice came out kind of muffled and since I'm not a native speaker, it got a bit hard at times. But it was worth going over it again.

A couple reflections:

I think here you can see why it doesn't matter: if she ever uses the guns, obviously she's getting no extra dice. They do "nothing" aside of performing the function of providing narrative context – sure thing, she can shoot someone from afar and thus be enabled to make a roll she may not have performed if she didn't have the guns… just like everything else that is rolled for based on what we said and done up to now; the guns are part of the context like buildings and cars and fireladders and whatever anyone introduced in the fiction without using any rule. This is all pretty obvious but it's still information: why does she has guns, and no dice to use with them? This can help us frame the narrative with it. Is she good with them? When she fails or succeeds, we can use this void space as information. If she put the guns but no dice in her character description… maybe she's still not expert in using them, but the guns are important. An heirloom? Just a manifestation of her paranoia? She doesn't get dice for using them, but could her behaviour be influenced by losing or dropping them? Does she act differently with her guns out?

Does this make any sense to you?

But it's undeniable that it's often labeled as "bad behaviour", distraction and other such things.

And it's interesting how people will go a long way to make sure someone who's not partecipating in a scene will not talk or provide comments. The most common example in my opinion is the "don't split the party" technique. It may seem like keeping everyone together boosts partecipation, but the reality is that most of the time what happens is that the GM is telling you "we're all together, so I'm talking to everyone, yes, I'm actually speaking with Steve and he's the only one who matters here, but stay in character and do nothing". By keeping everyone together, you exert control over their voice. Of course this isn't always (or often) the case, but I've been heard enough "Are you actually saying this? They can hear you?" passive-aggressive rebuttals to think it's not rare either.

But another interesting case this got me thinking about is those games that give a specific (often inconsequential but extremely regulated) role to people not partecipating in the scene. Lovecraftesque (and the strongly inspired Don Quixotesque) immediately come to mind, Polaris too in a way – I've often felt that these peripheral, "audience" roles serve the function of keeping people busy and shooting down this type of partecipation. It may be a good thing if the game requires or benefits from a strong focus on everyone's partecipation (even the silent type, and I would put Polaris in this group); but playing those games in the audience role I often felt like I couldn't really play and I couldn't really talk and the striking thing was that the things I was allowed to decide and say felt less impactful (not just in terms of enjoyment but also of affecting everyone's experience) than this type of "peanut gallery" parteciption.

It’s interesting that you

It's interesting that you mention games that give a specific role to players not directly involved in the scene. In my recent experience playing around with the Pool, I've thought about formally assigning those kinds of roles, with more specific tasks or domains of responsibility. However, as with all of the structural changes/additions to the Pool that I've contemplated, I've rejected them in favor of retaining the baseline expectations/structure, but then encouraging people to join the peanut gallery. I hadn't quite articulated to myself my reasons for rejecting those kind of more specific roles, but I think you are onto something: that they may paradoxically serve a purpose of diminishing meaningful participation.

Regarding Gratitude's derringers: it's funny because I can't imagine balking at Sam just being able to say she has them despite them not being words in her story, because it makes perfect sense that she would have them. On the other hand, if he had said she also had a military-grade armored assault vehicle in her garage, I probably would have said no. As I see it, we've got the story, which tells us which details are definitely in play, but then there's a larger set of possible props, sets, characters, and themes that are implied by the story. Those are fair game for anyone to bring in, based on what makes sense according to (a) the idiom of play and (b) what has thus far been established. The Pool gives us the opportunity to make them stick by allowing players to write them into their story as the game continues. (This is similar to how character development works in Champions Now and the earlier Champions tradition that it draws upon).

An example of this from the Napoleonic game that I have been GMing: one of the characters has become, due to the actions and events of the story, a general in command of a large army. However, the player hasn't written anything about being a general or being an army commander into his story (and therefore doesn't have any traits related to generalship or commanding troops or military strategy) which has a number of obvious and not-so-obvious effects. On the obvious side, he's only able to get extra dice during military-style conflicts if one of his other traits is somehow in play: there's an army at his command, which gives him a certain scope of action that he wouldn't have without it, but unless its use is tied to one of his other traits, he's limited in conflicts to the GM dice and what he gambles from his pool. Not-so-obvious: there's a way that by leaving that out of the written story, the player is making a statement that being a general/being in charge of an army is just not what this character is really about.

I want to focus pretty hard

I want to focus pretty hard on your point #1, which may help to show just what "an authority" is.

I'll take the example from play when I chatter about Amos Zag's appearance: from a party-ish counterculture guy with a handlebar mustache to his older, more heavy-featured face with no mustache and waved hair. What may not be evident is that all such chatter means nothing in our game in terms of content. It is not even a suggestion. Hold that thought, it's important.

This is because Amos is Jon's job. He is to say what Amos looks like, is like, is located, wants, has done, and does. This doesn't change no matter what anyone else says. If he had already settled into an idea of Amos as a huge, impassive, bald, toadlike man of indiscernible age, with a wart on his eyelid, then my comment becomes a brief bit of yap with the minor function of providing a moment for Jon to tell us what Amos really looks like instead.

This means two important things:

Jon's comment above about the derringers is pretty meaty in this regard – notice that he says outright, and accurately, that he has the job of deciding whether they exist. Sam's initial mention of them is like my description of Amos. It is within Jon's job to decide whether Gratitude has a derringer, or if Sam's comment might be converted into her thought balloon that she wished she had one, or if the comment is merely the minor sharing I describe above. I could go on: the description of the transit-station bar, the smash-cut after getting evicted, the guys at Gratitude's place, how drunk Star was, and more.

What I'm saying: don't mistake the happenstance that Jon does say, sometimes, "yes, that's what Amos looks like," and "sure, you've got a derringer" for the outcome of a negotiated proposal. Sam and I have no negotiating positions when we do this, and it's not up to Jon to accept or reject, but instead to intuit for himself what he feels like doing with non-actionable chatter. We do this a lot in this game, so it's easy to get the wrong impressions that either we're all just improvising together, riff-riff-riff, or Sam and I are constantly pitching how-abouts as dedicated content suggestions.

Please note that Sam and I do have our own authorities too, whether inside situations (e.g., where Willy goes after being evicted from Eddy's place – thanks, Maude) or, obviously, moments of narrating outcomes. We might talk about that later.

Session 2!

Gratitude digs herself deeper into a hole while Willy seems maybe to have clambered onto the edge of his. Check it out here.

I want to consider the ways that player input creates backstory in our game. It happens a lot: in my case, by inventing just enough content for my success in a certain roll to make usable sense, and in Sam's, by describing things which seem to him reasonable given what we know about Gratitude already. What are our parameters or principles for doing this? I am not too sure, and am reluctant to punch in too much, i.e., any more, as we go along. This session seems to me to have added a lot of pasta and tomatoes that Jon is expected to turn into spaghetti.

If possible, Jon and Sam can take the lead for that topic, so my own perceptions aren't setting the context.

Different ways to bring backstory into play

First, I just want to be clear about what is not happening: it is not the case that using a monologue of victory gives players backstory authority. However, in order for some successes to make sense, we are required to bring forward additional context – sometimes this context can come directly from the GM’s prep or the characters’ stories; sometimes it is implied by the prep, the stories, and what has been established already; and sometimes it is brand new material, inspired by the idiom. When I’m GM’ing, I’m preferentially bringing in material that is more grounded in prep or what has been established, and am only going to bring in new material as a last resort. Those preferences/principles are there to act as a buffer against slipping into a GM'ing mode where I am doing Intuitive Continuity.

With that in mind, here’s how the two examples Ron mentioned from our session look from my perspective:

With regard to Willy’s successful roll while attempting to reach out to a potentially sympathetic person in Amos Zagg’s organization, I did have a constellation of characters surrounding Zagg sketched out with brief descriptions and basic motivations. I was able to look that list over to see if any of them made sense to be that sympathetic person. In this case, it did make sense that one of these characters (I don’t think I mentioned her name in the session, but it is Lena Boch) would both be in a position to have gotten the email and be willing to act on it out of motivation of wanting to protect potential future victims.

Gratitude’s case is different: though having a crew of fellow thieves that she had worked with certainly makes sense given what we know of her from her story and from what we have established, I did not have them prepared in any way. (I did have a number of notes on characters connected to her dead gangster husband, but Sam was specific that Gratitude’s crew was separate from her husband’s life.) In this case, I needed to come up with characters in that moment that could fit into the space created by Sam’s request and my understanding of the ongoing situation and the idiom of the game as a whole. I quickly sketched out two more characters (Ray and Polly) and just as with the characters I had prepped ahead of time, gave them a brief description and some basic motivations to guide my play. A perhaps important point: I wanted to make sure I had at least a basic handle on their attitudes and motivations before starting the scene with them, so that I would have something to ground any decisions I made about how they would react to Gratitude’s pitch.

From the perspective of actually playing through these scenes, it doesn’t seem to make a difference if I am (a) playing a character that I developed prior to the session starting in more or less the way I had expected them to come onto the scene (which would be the case with the scene between Gratitude and Star in this session), (b) playing a character that I developed prior to the session who has been pulled into play in a way that was triggered by a character action that I could not expect and, more importantly, that I should not be trying to expect (Lena Boch making contact with Willy when he reached out), or (c) playing a character that I developed on the spot in reaction to what we established during the process of scene framing (Gratitude with Ray and Polly).

On the one hand, it seems to me that an overreliance on (c) would lead to a situation where there is very little genuine continuity from scene to scene; the consequences from one scene not really carrying over to the next one, because we are too often bringing in completely new material. On the other hand, it still doesn’t necessarily seem to me that the question of whether the characters were created on the spot or whether I am drawing them from my notes is the main issue: after all, the same effect would be created if I kept bringing in different characters from my notes into play and did that at the expense of following up on consequences of prior scenes and reincorporating elements that had already been established. (Which was actually a problem I ran into during the long Sorcerer game I ran a few years ago: throwing too many bangs early on, so that things felt disconnected and overly busy).

So I think the real issue is perhaps not so much the how, where, and when that backstory is created and/or brought forth into play, but rather how much is brought into play. If we are just bringing backstory into play (whether done through bangs, through the process of scene framing, from the process of narrating a success or failure) then that will act as an obstacle to consequential play going forward.

I agree! Toward the end of

I agree! Toward the end of the session, and again as I was editing, I felt uneasy or at least a little off about how much you were suddenly having to field. That's the only thought or concern or whatever we call it underlying my point in the post. I suppose it's the good kind of problem to have, given your points about the process, but I found myself wanting you to have downtime to process it. This is quite selfish, you understand – the more fully you can bring Bulwark City down on us, the better. I'm glad we're playing such short sessions.

Session 3

I felt that things really popped into focus during this session, at least in part due to me not having to bring in any new elements and being able to work completely from things that had been prepped and/or established by us already during play.

Here's what went into my preparation for our third session:

For Willy, I had to ask "what would Lena do next?" Given that I was bound to honor both (a) Willy's successful roll that led to her having sympathy for him and for the killer's victims and (b) my initial conception of her as being loyal to Amos Zagg, it made perfect sense that she would want to get Zagg himself involved: that way she could feel that she had done something to protect further victims while at the same time not potentially jeopardizing Zagg's political ambitions.

Note that at no time did I ask (or have to ask) whether or not it was the right time, in terms of some sense of pacing, to bring Zagg onscreen. In this game, given how Ron has played Willy, given the results of his rolls, and given the relevant details of the situation I had prepped — of course Zagg has to show up now.

I'd also note that I decided to narrate it that Willy knew that he failed to convince Zagg, rather than him being oblivious to it, mainly because it seemed like someone as paranoid as Willy would pick up on something like that.

For Gratitude, as I tried to make clear, I did not want us to turn the heist into a mini-wargame, where Sam would be expected to try to plan a perfect caper. Rather, I wanted to make sure we had enough context so that (a) Sam could make some meaningful decisions and (b) we'd have enough fictional stuff in place to soundly ground any outcome narrations. The relevant elements that bound my presentation of this context included (1) Willy's successful roll using his "screw everything up" trait, (2) Gratitude's turn on Star at the end of Session 2, and (3) Gratitude's failure to keep Ray and Polly in the dark about the nature of the job.

I'm excited to see what happens next for both of them!

Do you mind drilling down a

Do you mind drilling down a little bit into how the heist went down? "Heist" is one of those genre-buzzwords that has a tendency to set certain expectations that can trigger disappontment when undermined. I don't think anyone in this group would have that problem but I am curious how the interplay of a heist-like situation and The Pool worked.

The term “heist” has

The term "heist" has remarkable black-hole sucking power. During this session, Gratitude and her partners gained access to Zagg's top-floor suite and became aware that two people were unexpectedly present … and that's it. As far as their access is concerned, the characters' competence was taken for granted and we specifically discussed that, to competent people, if a given robbery was hard or featured known moments of considerable risk, they wouldn't do it. That included some joking about how likely three non-robber role-players were to have any clue about actual techniques, i.e., not at all. Therefore what can only be called Hollywood heist porn was absent from play, and if I'm remembering correctly, no roll was involved.

Tommi and I discussed the heist issue relative to role-playing at his post from about a year ago, in the comments here. I stress again that it was singularly not relevant to our current game.

To summarize events of the

To summarize events of the session, briefly anyway:

Several useful points are evident in how we did these things and how they came about. The main one is probably that several earlier rolls had slow-burn results, e.g., the reason the creepy twins are in Zagg's apartment and not, for example, killing Willy, is that Willy's contact with Lena in session 2 included causing some kind of inadvertent trouble for someone else, via the trait being used. This is the result of the trouble. It also leads to the parallel activity that Willy is running all over his hotel trying to see if the twins are there and how they might come to get him, planning escape routes, et cetera, whereas the twins are not there at all and actually providing Gratitude and her partners with very terrible danger in a silent, dark suite.

Both Sam and I have arrived at a sense of our characters' mannerisms, and one reason I'm pissed-off at losing this video is that both of them "jumped up" in terms of seeming to play us rather than the other way around. For myself, I quite like Willy's essentially harmless nature … but especially having realized that Zagg is a dangerous prick, somehow managing to hold onto a sense of purpose about the murder victims. Sure, it may have begun as wanting to feel important, but it seems to me a dim little coal somewhere in his nigh-worthless existence just received a bit more oxygen.

To expand a little on what

To expand a little on what Ron wrote about the break-in at Zagg’s apartment:

The way I’ve started to approach scenes like this has been heavily influenced by how we’ve been playing Champions Now (the most recent post about that is here, but this reminds me I'm due for an update). When we started in Champions Now, the players all got really involved in planning out missions like a special forces team: the game supports that kind of play and it also supports not doing it. So, when one of the players said that they felt they were getting bored by all the planning, I reminded them that we don’t have to do that: that we can directly use the rules for skill use (especially Detective, Stealth, and Security Systems), related powers (Awareness, Invisibility, Desolidification), and, of course, Luck and Unluck, in a way that lets us figure out the relevant parameters of the upcoming scene (mainly, but not solely, relating to the question of who has the jump on whom).

This, of course, happens in the source material all the time: in To Live and Die in L.A., for example, we don’t see Chance and Vukovich plan the robbery, and, in fact, the last time we saw Vukovich before the robbery scene starts, he wasn’t even committed to going along with it. I also really took to heart a moment in one of James Robinson and Tony Harris’ Starman comics: there’s a sequence dealing with the Golden Age Starman and his allies where they are discussing coordinating their efforts against a broad range of threats. We go instantly from a panel where Doctor Midnite says something like, “I’ll track down the kidnapped kids, that seems like something up my alley” to a panel where he’s ambushing the kidnappers in their hideout. It doesn’t necessarily need to matter how he tracked them down: that he did so is what’s important.

For this game, I did want to give Sam a few options, in part to provide a little more bounce off of my preparation: and so Sam had the option of having Gratitude go in earlier in the night (potentially more general traffic but being pretty sure that Zagg would not be there) or later in the night (less traffic, but Zagg present), as well as a general choice of how to make entry (dealing with the security guard versus sneaking around the security guard). But those options were not presented as a puzzle to be solved or a situation to wargame: rather, they were there to provide context and material for saying how things happened.

Sam did make one roll here because there was uncertainty involved, but the uncertainty was not necessarily all about “how does Gratitude handle the nuts and bolts of the break-in”. This is a tricky point because I want to also note that we did not pre-negotiate any of the possible outcomes which meant that the narration of the roll (in this case a successful roll that Sam had me narrate so he could take the extra die) wasn’t forced to go down a particular route. The main benefit of that success ended up that Gratitude didn’t walk headfirst into the unexpected-by-her additional guards.

Cool. It’s because “heist” is

Cool. It's because "heist" is such a blackhole of a word that I was asking. So, I was curious where along the event horizon this was crusing. I see now that it was more like a straight-foward burglary type situation than, say, a clever series of ruses, distractions and reversals. That makes sense especially in context of everything else going on in this game.

Session 4!

Preceded by a brief summary of events in session 3. Here's the link.

We've hit a plotwise turning point, I think. Both Gratitude and Willy are in extremely different circumstances from their starting points, as well as affecting one another's problems without realizing it.

I am especially sad that the borked recording of session 3 cannot show Jon's portrayal of Amos Zagg: tremendously reassuring, responsible, thoughtful, and far-seeing … and completely terrifying. That presence looms over both characters in session 4, unknown to Gratitude and all too well-known by Willy, at this point.

GM Agency vs. GM Fiat

I wanted to call attention to something in this latest session that Ron and Sam and I discussed in our post-game chat:

After Sam failed his roll and Gratitude ended up at the mercy of one of the Twins, there was a bunch of stuff that was left hanging that I, as a GM, just had to make up my mind and handle. Specifically (as Sam reminded me), I had to figure out what would come about through the interaction of three NPCs (the Twins and Polly).

The Pool does not have additional specific procedures to guide or constrain the GM’s choices in situations like these: you are left to your own devices, pursuing your own aesthetic, and maybe you are following some principles – but there aren’t, as we might have in many other games (from Holmes Dungeons & Dragons to Sorcerer and beyond), NPC vs. NPC conflicts that are handled by rolling dice.

I first started thinking about this kind of issue when playing Legendary Lives, where the procedure for NPC vs. NPC (called Foe vs. Foe in Legendary Lives) conflict is as follows (p. 162 in the pdf I have):

Italics mine – that’s the piece I wasn’t really comfortable with in Legendary Lives, and so I developed a principle that in any foe vs. foe conflict I would first be guided by the logic of the situation (comparison of the foes’ various ratings for defense, skills, and combat; taking actions that followed from known events and/or known things about the foes’ motivations and personalities) but that after I had accounted for the logic, I would try to push for the outcome to be as bad for the players as possible (i.e., things would go worse for the NPCs who were allied to the PCs or about whom the PCs cared about in some way). This was partly to get across that in our game of Legendary Lives, the player characters could not rely on NPCs to pull their fat out of the fire. I wanted it to be clear that if the players wanted something to happen they would have to take action. That was an aesthetic/literary choice on my part: you could set this dial someplace else and that would create a different kind of story than what we ended up with.

That’s kind of what I am trying to do in how I play the Pool now, too: things will get worse for the player characters unless they do something about it. They can’t rely on NPCs alone to solve things for them, though they can inspire or order or take charge of NPCs to get them to act effectively. In our recently concluded Napoleonic Fantasy game, there was a lot of NPC activity that was directed by the player characters and thus was dealt with as part of the players’ conflict rolls.

I think this opens up a big topic, as Ron has mentioned, gets us to start looking at what GM agency might look like: i.e., the choices I made here with regard to the Twins and Polly are not the choices Ron or Sam would have made if they were in the GM’s seat, with the GM’s particular authorities and responsibilities. This isn’t GM fiat, as the GM doing this task is necessary for play to happen in these games, but I think it can look like GM fiat – or the GM taking inappropriate control over things – from a distance or from the point of view of a player who has had bad experiences with over-controlling GMs in the past.

Session 5

Here's the link! Gratitude and Willy are finally in the same place at the same time, causing plenty of trouble in their respective inimitable ways.

Warning: Gratitude solves a problem in a fashion which even I might call "offensive," so although I think it is totally on-point with this game and these themes, well, now you know.